Medieval era[edit]

Astrolabes were further developed in the medieval Islamic world, where Muslim astronomers introduced angular scales to the design,[16]adding circles indicating azimuths on the horizon.[17] It was widely used throughout the Muslim world, chiefly as an aid to navigation and as a way of finding the Qibla, the direction of Mecca. Eighth-century mathematician Muhammad al-Fazari is the first person credited with building the astrolabe in the Islamic world.[18]

The mathematical background was established by Muslim astronomer Albatenius in his treatise Kitab az-Zij (c. 920 AD), which was translated into Latin by Plato Tiburtinus (De Motu Stellarum). The earliest surviving astrolabe is dated AH 315 (927–28 AD).[19] In the Islamic world, astrolabes were used to find the times of sunrise and the rising of fixed stars, to help schedule morning prayers (salat). In the 10th century, al-Sufi first described over 1,000 different uses of an astrolabe, in areas as diverse as astronomy, astrology, navigation, surveying, timekeeping, prayer, Salat, Qibla, etc.[20][21]

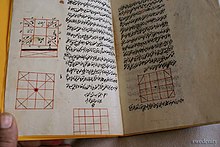

The spherical astrolabe was a variation of both the astrolabe and the armillary sphere, invented during the Middle Ages by astronomers and inventors in the Islamic world.[c] The earliest description of the spherical astrolabe dates back to Al-Nayrizi (fl. 892–902). In the 12th century, Sharaf al-Dīn al-Tūsī invented the linear astrolabe, sometimes called the "staff of al-Tusi", which was "a simple wooden rod with graduated markings but without sights. It was furnished with a plumb line and a double chord for making angular measurements and bore a perforated pointer".[22] The geared mechanical astrolabe was invented by Abi Bakr of Isfahan in 1235.[23]

Herman Contractus, the abbot of Reichman Abbey, examined the use of the astrolabe in Mensura Astrolai during the 11th century.[24] Peter of Maricourt wrote a treatise on the construction and use of a universal astrolabe in the last half of the 13th century entitled Nova compositio astrolabii particularis. Universal astrolabes can be found at the History of Science Museum in Oxford.

English author Geoffrey Chaucer (c. 1343–1400) compiled A Treatise on the Astrolabe for his son, mainly based on Messahalla. The same source was translated by French astronomer and astrologer Pélerin de Prusse and others. The first printed book on the astrolabe was Composition and Use of Astrolabe by Christian of Prachatice, also using Messahalla, but relatively original.

In 1370, the first Indian treatise on the astrolabe was written by the Jain astronomer Mahendra Suri.[25]

A simplified astrolabe, known as a balesilha, was used by sailors to get an accurate reading of latitude while out to sea. The use of the balesilha was promoted by Prince Henry (1394–1460) while out navigating for Portugal.[26]

The first known metal astrolabe in Western Europe is the Destombes astrolabe made from brass in tenth-century Spain.[27][28] Metal astrolabes avoided the warping that large wooden ones were prone to, allowing the construction of larger and therefore more accurate instruments. Metal astrolabes were heavier than wooden instruments of the same size, making it difficult to use them in navigation.[29]

The astrolabe was almost certainly first brought north of the Pyrenees by Gerbert of Aurillac (future Pope Sylvester II), where it was integrated into the quadrivium at the school in Reims, France sometime before the turn of the 11th century.[30] In the 15th century, French instrument maker Jean Fusoris (c. 1365–1436) also started remaking and selling astrolabes in his shop in Paris, along with portable sundials and other popular scientific devices of the day. Thirteen of his astrolabes survive to this day.[31] One more special example of craftsmanship in early 15th-century Europe is the astrolabe designed by Antonius de Pacento and made by Dominicus de Lanzano, dated 1420.[32]

In the 16th century, Johannes Stöffler published Elucidatio fabricae ususque astrolabii, a manual of the construction and use of the astrolabe. Four identical 16th-century astrolabes made by Georg Hartmann provide some of the earliest evidence for batch production by division of labor.

No comments:

Post a Comment